Battle of Beersheba 1917

The decisive victory at Beersheba was achieved through one of history’s last great mounted troop charges, led by the Australian Light Horse Divisions. Years later, this event was immortalized in a film. The charge, taking place on October 31, 1917, was a pivotal moment in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign during World War I. The bold and unexpected manoeuvre caught the Ottoman forces off guard, leading to a significant breakthrough for the Allied forces. The success at Beersheba not only demonstrated the enduring effectiveness of cavalry in modern warfare but also boosted morale among the troops. The story of the Australian Light Horsemen and their daring charge continues to be celebrated as a testament to bravery and strategic innovation.

Many years later it was made into a film.

As the sun dipped below the horizon on October 31, 1917, the Negev Desert witnessed an extraordinary moment in history. The Australian Light Horse Divisions charged into action, capturing the town of Beersheba in a dramatic conclusion to a crucial battle in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I. This daring assault marked a significant turning point for the Allied forces against the Ottoman and German Empires in the Middle Eastern theatre. The Battle of Beersheba not only demonstrated the power of Maneuver Warfare but also showcased the remarkable ability of mounted troops to decisively change the tide of battle, especially when charging into battle on a horse had become outdated

On October 31, 1917, amidst the arid expanse of the Negev Desert, just north of the Sinai Peninsula, a dramatic showdown unfolded. The British, Australian, and New Zealand forces, united under the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, launched a relentless, day-long assault to seize the strategic town of Beersheba. This triumphant victory became a turning point in the epic Sinai-Palestine Offensive, a campaign that had gripped the region since January 1915 when the Ottoman forces first launched raids on the Suez Canal.

Following the successful capture of Jerusalem, the Allied forces maintained their momentum, steadily advancing through the region. Their strategic manoeuvres and coordinated efforts weakened the opposition, enabling them to secure key territories. This offensive not only bolstered the morale of the Allied troops but also significantly shifted the balance of power in the region. The campaign’s success laid the groundwork for further advances, ultimately contributing to the broader objectives of the Allies in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I.

The Armistice of Mudros marked a significant turning point in the Middle Eastern Theatre of World War I. With the Ottoman Empire’s grip loosening, Allied forces gained a strategic advantage, paving the way for new political landscapes in the region. The surrender of Ottoman Syria and Palestine territories not only signified a military victory but also set the stage for the post-war reorganization of the Middle East. As the Ottoman Empire teetered on the brink of collapse, the Allied powers began to envision the division of its vast territories, leading to the eventual establishment of new nations and borders that would shape the geopolitical dynamics of the 20th century. The events following the Battle of Beersheba and the Armistice of Mudros underscored the shifting balance of power, laying the groundwork for the modern Middle East.

Manoeuvre Warfare’s effectiveness was further demonstrated in subsequent operations, where speed and surprise continued to play pivotal roles. The success at Beersheba set the stage for a series of victories that would eventually lead to the capture of Jerusalem. The ability of mounted troops to rapidly exploit weaknesses in enemy defences became a hallmark of the campaign, with the Australian Light Horse and other cavalry units frequently at the forefront.

The victory at Beersheba also underscored the importance of logistics and resource control in warfare. Securing the water wells not only deprived the Ottoman forces of essential supplies but also ensured the advancing Allied troops could sustain their momentum in the arid environment of Southern Palestine. This strategic advantage allowed General Allenby to maintain pressure on the retreating Ottoman forces, preventing them from regrouping effectively.

As the campaign progressed, the lessons learned at Beersheba were applied to subsequent battles, with commanders increasingly relying on the mobility and shock value of mounted troops. The integration of artillery support with cavalry operations became a key tactic, allowing for quick, decisive actions that minimized prolonged engagements and reduced casualties.

In the broader context of World War I, the success of the Beersheba operation demonstrated the enduring relevance of cavalry in modern warfare, even as mechanization began to transform military strategies. The adaptability and courage of the Australian Light Horse and their counterparts were instrumental in reshaping the dynamics of the conflict in the Middle East, contributing to the eventual Allied victory in the region.

By the middle of 1917, as the Third Ypres Offensive began on the Western Front, the heart of the Ottoman defensive position in southern Palestine was the coastal city of Gaza. Stretching southeast of the city for nearly 50 kilometres was the Ottoman’s defence line against the British advance northward into Palestine. At the end of this line lay Beersheba. Earlier in the year, the first and second battles of Gaza failed to secure the city, which had instead become more heavily fortified after each attack. Progress north into Palestine, toward Jerusalem and beyond, had completely stalled.

The town was defended by lines of trenches on its western, southern and to a lesser extent eastern outskirts, supported by shallower trenches and small fortified redoubts, in reality little more than earthen mounds.

Highpoints, such as the top of small hills were also used and this covered all approaches to the town. There were, however, little or no wire defences for the attackers to deal with. From the vantage of hindsight, Beersheba seems poorly defended for a location of such strategic importance. Ottoman forces garrisoned at Beersheba were indeed well under strength. Not only was Beersheba the strongpoint of the eastern end of the Ottoman defensive line, but the town also contained 17 water wells, and a major railway junction, intersecting with the Hebron Road.

Approving the plan, Allenby directed Lieutenant Generals Chetwode commanding the British Twentieth Corps, and Chauvel, the Anzac Desert Mounted Corps, to take Beersheba, before attempting another attack on Gaza.

Utilising Chetwode’s plan, Allenby believed victory at Beersheba would be the catalyst that would break the stalemate which had faltered the Allied advance.

Critical to its success would be to execute the attack in a day, to avoid the destruction of the wells, which would cripple the significance of the victory.

Mindful of this, the plan called for a concerted artillery and infantry attack on the town’s western side, with two British divisions pressing the advance on the main entrenched Ottoman defences. At the same time, ANZAC Divisions, principally made up of cavalry brigades, would take key positions in the east, to then be in a position to sweep into the town centre.

Four understrength divisions of the Ottoman 3rd Corps awaited them, distributed to the west, south and east of the town. Of those, the 27th and 16th Divisions would bear the brunt of the British advance, while the 24th Reserve Division would face the ANZAC mounted troops.

In case of defeat, Ottoman forces would retreat north, ensuring the destruction of the town’s Water Wells as they went.

Manoeuvre warfare tactics began in the second half of October, including six days of Allied artillery bombardment at Gaza, as a diversion to keep Ottoman reinforcements away from Beersheba.

A misinformation campaign also planned to convince German and Ottoman commanders that the next British attack would fall again on the coastal city. Meanwhile British and Anzac Divisions made ready in the east, for what would be the real opening to the Third Battle of Gaza.

Just before 6 a.m. on the morning of October 31st, 1917, Lieutenant-General Sir Philip Chetwode ordered British artillery to begin a bombardment of the main Ottoman trench line in front of 20th Corps, on the west and southwest outskirts of Beersheba.

Around one hundred field guns and howitzers fired on all Turkish positions, about twenty specifically targeting the enemy’s artillery batteries, while the others sent high explosives and shrapnel over the advanced, Ottoman trench lines.

Trooper Ion Idriss, of the 45th Australian Light Horse, observed, “Above the far-flung redoubts floated shrapnel-puffs, while clouds of smoke masked the trenches. The shells exploded sharp and clear.”

With dust and smoke filling the air and obscuring targets, units of the 60th London Division attacked Hill 1070, directly ahead of the main Ottoman front line.

Meanwhile, the 74th Yeomanry Division edged forward, and by noon had captured their objectives, suffering 1100 casualties in the process.

From 9 am, in the northeast of Beersheba, units of the Anzac Mounted Division moved forward to block the Beersheba Hebron Road at Tel El Sakati and take the small hill there. They would then advance on the larger Ottoman position at the top of Tel El Saba. This manoeuvre would block both an enemy retreat as well as any enemy advance from Hebron and remove an Ottoman position that dominated the eastern side of Beersheba.

The momentum of the Allied assault continued as the 2nd Australian Light Horse Brigade took Tel El Sakati, before faltering as Ottoman forces at Tel El Saba successfully resisted the Anzac Mounted Regiments’ attempts to take their position of high ground, until after 2.30 in the afternoon.

Soon after Tel el, Saba was taken, Major General Chaytor moved his Anzac Mounted Division’s field headquarters into the settlement. Almost immediately, Ottoman artillery began targeting the new position, and German aircraft dropped bombs. These intense aerial attacks would continue throughout the afternoon.

From Tel El Saba, Chaytor ordered the 1st and 2nd Light Horse Brigades to begin a dismounted advance on Beersheba, toward the mosque, joining other Brigades in their moves to close in on the town. It would take them a little over 2 hours to reach the area surrounding the mosque, advancing under Ottoman artillery.

By 4 pm, the third and final phase of the Battle of Beersheba was poised to begin, as Brigadier-General William Grant ordered the 4th Australian Light Horsemen to ‘saddle up’ and move into attack formations.

Unknown to Allied command, the Ottoman garrison commander, Ismet Bey, recognising impending defeat, ordered a general retirement of the garrison northwards, and the destruction of Beersheba’s water wells.

The Ottoman 8th Army’s German commander, Kress von Kressenstein, would later conclude that “Beersheba was now untenable and unknown to the attackers, a withdrawal was ordered. The understrength Turkish battalion entrusted with its defence doggedly held out with great courage and in so doing fulfilled its obligation. They held up two English cavalry divisions for six hours and had prevented them from expanding their outflanking manoeuvres around the Beersheba-Hebron Road.”

At around ten past 4 in the afternoon, Victorian men of the 4th and News South Wales men of the 12th Australian Light Horse Regiments moved through the Wadi Abu Sha’ai and formed up behind a ridge and astride a track known as the “W” road. They were six and a half kilometres outside Beersheba.

Three kilometres south-west of their position, the 11th Light Horse Regiment were ordered to follow the 4th and 12th in reserve.

Each regiment was divided into three squadrons of around 128 men each and allotted 200 metres of the front line. These ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ squadrons were arrayed between 270 and 460 meters apart to allow them to spread out once the charge began.

Brigadier-General Grant observed, “It was essential that the place be taken quickly, as the horses had not been watered since the previous day and had made a night march of over thirty miles … only a little over an hour of daylight remained in which to carry out the operation.” Just before half-past four, Brigadier-General Grant, leading at the front, ordered the 4th and 12th Light Horse Regiments to move off. Personally addressing his troopers, Grant told them, “Men, you are fighting for water. There’s no water between this side of Beersheba and Esani. Use your bayonets as swords. I wish you the best of luck.” And with that, the charge commenced at a gentle walk.

They are followed by the 11th Light Horse, accompanied by the 5th and 7th mechanized Battalions which would provide artillery support for the charge.

After five minutes, the pace of the charge lifted to a trot, with each horseman now four metres apart from his fellow trooper.

Scouts were ordered forward to reconnoitre for obstacles such as barbed wire and natural features that might hinder their advance.

Having led the advance to a trot, Brigadier-General Grant fell back to a reserve position in order to direct the subsequent action, while the 4th and 12th Light Horsemen moved within range of the Ottoman front line, before the eastern perimeter of Beersheba. From their positions within the trenches, Ottoman defenders sighted the advancing cavalry in the distance and opened fire with artillery and rifles.

The 4th and 12th increased their speed to a gallop, now 2 kilometres from the Ottoman front line, as two German aircraft attempted to disrupt the charge, dropping bombs amidst the horses. However, the speed and distribution of the Light Horse charge proved a challenging target. As the pace of the charge intensified, time was measured in minutes and seconds.

Trooper Ion Idriss later described the scene: “They emerged from clouds of dust, squadrons of men and horses taking shape. All the Turkish guns around Beersheba must have been directed at the menace then. Captured Turkish and German officers have told us that even then they never dreamed that mounted troops would be madmen enough to attempt rushing infantry redoubts protected by machine-guns and artillery… their thousand hooves were stuttering thunder, coming at a rate that frightened a man — they were an awe-inspiring sight, galloping through the red haze — knee to knee and horse to horse — the dying sun glinting on bayonet-points.”

As the charge increased, rapidly approaching the outlying defences, British infantry to the southwest of Beersheba mounted a concerted attack. Vigilant British artillery officers targeted and silenced Ottoman positions on the approach to the town, which was firing on the 12th Light Horsemen as they closed on Beersheba.

The charge was now sustaining a steady rapid-fire from the shallower advance enemy trenches, about one and a half kilometres away. Some horses in the advanced line were hit and fell, but the charge did not falter.

A mere 400 metres from the enemy line, at full gallop, bullets flew past the Light Horsemen and their mounts. In their rush to respond to the rapidly changing positions, the Ottoman soldiers failed to adjust the range of their sites and their bullets cut the air above the charge.

Trooper Chook Fowler recalled, “As we came closer to the trenches most of the fire went over our heads. The Turks must have forgotten to change their sights. Our Squadron was drawing closer and looking down I saw a line of Turks lying on the ground and firing their rifles; my horse had to jump to one side to miss them.”

Lieutenant Colonel Bourchier, commanding the 4th Light Horse reported that “the morale of the enemy was greatly shaken through our troops galloping over his positions, thereby causing his riflemen and machine gunners to lose all control of fire discipline.”

Almost at the same time, the 4th and 12th Light A Squadron jumped the first occupied trenches. Troopers dismounted and faced the entrenched enemy in intense standoffs, resulting in fierce close-quarter combat and Ottoman surrender.

Alfred Healey and Thomas O’Leary, both scouts of the 4th, were first to jump the Ottoman trenches. Whilst Healey dismounted to take prisoners, O’Leary charged ahead and on into the town.

The Official Australian History records that, “O’Leary jumped all the trenches and charged alone right into Beersheba. An hour and a half afterwards he was found by one of the officers of the regiment in a side street, seated on a gun, which he had galloped down, with six Turkish gunners and drivers holding his horse by turn. He explained that, after taking the gun, he had made the Turks drive it down the side street so that it should not be claimed as a trophy by any other regiment.”

As the main body of the charge made contact with the trenches, Lieutenant Colonel Donald Cameron, commanding officer of the 12th Light Horse later described how, “On reaching a point about 100 yards from these trenches, one Troop of ‘A’ Squadron dismounted for action, and the remainder of the Squadron galloped on.” This tactic was used by ‘B’ and ‘C’ squadrons, while the main strength of the regiment charged on into Beersheba. Ottoman soldiers in the advanced trench lines now faced Australian Light Horsemen in front and behind their position.

Having jumped the trenches, Lawson and Hyman, both leading squadron commanders, attacked from the rear. One ‘B’ Squadron Trooper, advancing on a reserve trench line closer to the town, had his horse shot from under him, as they vaulted over the enemy. As he rose from the ground, dazed by the fall, he was surrounded by Ottoman soldiers with their hands in the air. Minutes behind the charge, stretcher-bearers rode up to the advanced lines to aid the wounded, while the vanguard of the attack had moved onto the main and reserve trench lines. Here Hyman led dismounted troopers in the fight. Sixty Ottoman soldiers were killed in close quarters, fighting until a surrender was reached.

Jack Davies, a captain in ‘B’ Squadron observed the ‘A’ Squadron attack, “Hyman was left with the troop of men who did dismount and most of our casualties were, I think, amongst them… Hyman and a few others accounted for 60 dead Turks, which was not bad seeing that they were in the open and the Turks were in a beautiful trench. All it lacked was wire and why they had not wired it, I don’t know.”

Davies himself along with fellow captain Robey charged toward Beersheba. Trooper Edward Dengate of the 12th Light Horse recalled, “Most of us kept straight on, where I was, there was a clear track with trenches on the right and a redoubt on the left, some of the chaps jumped clear over the trenches in places, some fell into them, although about 150 men got through and raced for the town, they went up the street yelling like madmen.”

Davis and Robey halted the charge at the junction of Asluj Road and the Wadi Saba, where they renewed their units’ attack formations. Together they approached Beersheba’s mosque, just before 5 pm, and then separated, with Davis leading his men up the main street of Beersheba, whilst Robey leads his Squadron to the northwest of the town.

As Beersheba fell to the advanced Squadrons of the 12th, enemy aircraft were inflicting a heavy toll on the Anzacs at Tel El Saba. These aircraft had been menacing their position all afternoon and now bombs killed and wounded many Australian and New Zealand men and their horses. By five minutes past five, Beersheba was almost completely surrounded and Light Horsemen had reached the centre. As Robey and Davis’ squadrons completed their circuit of the town, they faced the Ottoman Withdrawal Column, with their nine artillery guns in tow. Without resistance, the Ottoman commander surrendered the entire column.

By 5:30 that evening, with dusk setting in, the town of Beersheba was under the control of the Desert Mounted Corps and British Divisions. Six hours of consolidation and rounding up prisoners ensued.

As night fell, Captain Davis recalled in a letter, “I had just finished counting my little lot of prisoners and sent them away under escort (it was a beautiful moonlight night and I counted them as a lot of sheep with Marnie and Haft keeping tally. 647 and 38 officers were the numbers as well as I remember the odd figures … 4th Light Horse got 350 odd more and we collected about 30 strays during the night.”

By 11 pm the Desert Mounted Corps HQ at Beersheba declared the town clear of the enemy.

After the battle, the Ottoman defensive line in southern Palestine began to collapse, as the Allied forces pushed it back to the coast and on into the north.

On the 6th November, one week after Light Horsemen and British infantry stood in the town square of Beersheba for the first time, General Sir Edmund Allenby wrote to his wife, “We’ve had a successful day. We attacked the left of the Turkish positions, from north of Beersheba, and have rolled them up as far as Sharia. The Turks fought well but have been badly defeated … Gaza was not attacked, but I should not be surprised if this affected seriously her defenders.” The following day, Allenby’s army occupied the city, concluding the Third Battle of Gaza.

Allied victory in the Middle Eastern Theatre of World War One, under the command of General Sir Edmund Allenby, contributed significantly to a defining era for the region.

Alongside T. E. Lawrence, well-known as Lawrence of Arabia, General Allenby commanded the British component of the Arab Revolt in the deserts east of his armies.

Allenby’s financing of this irregular, but often wildly successful force, extended his preference for the agility of manoeuvre warfare and contributed decisively to his overall successes.

Eleven months after the Third Battle of Gaza, 160 kilometers north east of the coastal city, the Ottoman line was broken at Megiddo, including a cavalry route to block the Ottoman retreat. The overall victory followed, as Australian forces, alongside British, New Zealand, Indian, South African and Prince Feisal’s Sherifial Hejaz Army seized first Damascus, then Homs and by the end of the month, Aleppo, at the very border of Turkey.

Shy of one day to the year that Beersheba had fallen to the Light Horse Brigade, the Armistice of Mudros brought an end to fighting in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I, and signalled the end of the Ottoman Empire.

Obscured by profound changes in the region, the Armistice finally fulfilled objectives given to Australians on their first foray into the conflicts of the first world war, where more than three years before, at Gallipoli, Anzacs were tasked with occupying the forts of the Dardanelles.

I find the attack fascinating, It was the last time cavalry would be used in such numbers and the tactics used to bring home the attack was sublime, to say the least. The attack came in so fast that the Turkish defences did not even have time to just their sights on both artillery and small arms. The first rank of Light Horse went over the trenches then unmounted their horses, and attacked from behind the second rank stopped short dismounted and attacked on foot. The tactic was so successful that only 31 men from the Light Horse were killed, 36 were wounded, 70 horses killed with over 60 wounded. They captured 1,000 Turkish soldiers. On the other side of the coin, the Ottoman casualties are believed to be about 1000 (killed and wounded). The British lost 171 troops killed in action earlier in the day attempting to take Beersheba. What is also fascinating is the choice of weapons used. Gone was the usual Sabre, also spelt saber, heavy military sword, in came the Bayonet held by the hand not fixed to the rifle It was perfect for thrusting in tight spots like in the Trenches that the Turkish soldiers were inIts no wonder they inflicted so much damage to the entrenched Turks that would have been using their rifles with fixed bayonets. In a tight spot like that the shorter bayonet was a godsend to the Australians.

What is also fascinating as well, is the fact that many of the Light Horse were veterans of the Gallipoli, campaign where they saw hundreds of their comrades lose their lives, then had to retreat back to Egypt in defeat licking their wounds. It must have been a bittersweet moment for them when they attacked those positions defeating their old foe.

I guess the lay of the land helped them as well, it was flat giving the horses the freedom to pick up speed. It also said that the horses could smell the water, which urged them on, this might be true as both men and horses had gone without water for at least a day as the water was in front of them and many miles behind them. I say this because when the Australians dismounted, their horses ran hell for leather to the water troughs in Bathsheeba its self.

The poem was written by 2639 Tpr Arthur Wilson Beatty soon after taking place in the charge at Beersheba.

BEERSHEBA.

(Written by 2639 Tpr Arthur Wilson Beatty, C Sqn, 4th LHR)

We left the “Wadey” at break of day,

We rode far into the night;

Our loads were heavy, our horses poor,

But we pushed them on as we’d done before,

And swallowed the dust, and growled and swore,

Till Esani came in sight.Two days we rested, three days we rode,

While the ‘planes buzzed overhead.

We left Khalasa at dead of night,

And we rode till dawn; then, streaked with white.

The mountains of Judah came in sight,

Like watchers o’er the dead.We kept our horses behind the rise,

We followed the “Wadey” round,

And sunset found us behind a hill,

Our horses tired, but ready still

To gallop again at their riders’ will,

And watch for the broken ground.Three miles of a wind-swept, shell-torn plain

Where death was sure to lurk!

The shrapnel screamed, the bullets whined,

Swift death spat out from the redoubts lined,

And red flame showed where the wells were mined

By the panic-stricken Turk.The sun set red as we galloped on,

Our ranks thinned here and there,

As one dropped out who would ride no more

And a groan, as somebody galloped o’er

A foeman, battered and sick an sore,

Surrendering in despair!

.

Onward we rode till we reached the town,

At the end of the three-mile plain.

Empty and burning the old town lay;

The foeman beaten, had slunk away,

And left us there at the dawn of day,

To follow, and fight again.The sun rose high on the saddest scene,

The last of the boys “gone West!”

They’d all gone out as the soldier dies -

We buried them out on a lonely “rise”

Where the mournful wind from the desert sighs

We left them there at rest.Perhaps a cross, or a row of shells,

On wind-swept dusty “rise,”

Will mark where a brave man left the race

With a willing heart and a smiling face -

His grave a Bedouin camping place -

But memory never dies!

Part of the charge. The photo was taken by a Turk. The Turk was later captured and the camera was confiscated. Many say this photo was taken after the charge in some sort of reenactment. I am not so sure because if you look above the riders you see three puffs of darkened smoke, those are shell bursts that are being fired above the riders to take them out with shrapnel.

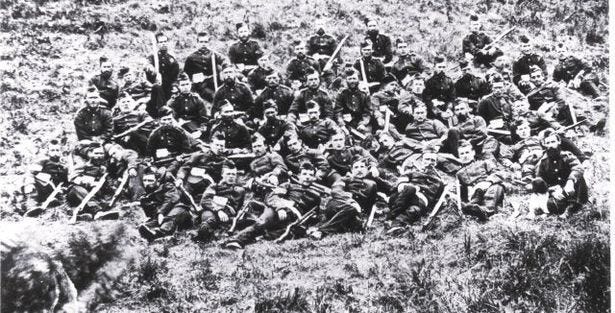

Moving up the line to attack positions

Arial photo of Bethsheeba from 1917

Bathsheba now